A Simpler Time

“Before the days of instantaneous uploading and retakes, there was me, and you, and a disposable camera. Cheap, rectangular plastic that housed grainy film. It didn’t matter if we blinked or if the angle was bad, or if your finger ended up in the top right corner. I always framed the best ones; not to protect the photo, but to protect the memory. It was a simpler time, which allowed for a simpler “us”, and we were simply happier then” – Alicia Cook.

When the printing press first emerged, people who were unable to read could suddenly learn how. No longer was communication reserved for only the rich and powerful, but the dissemination of printed documents “went viral.” Transparency spread, a new wave of accountability was ushered in, kings were slain and governments fell. The new means of communication forever changed humanity.

From a hilltop in England overlooking the sea, countrymen spotted the masts of 151 ships of the Spanish Armada heading directly toward the coast. As the sun began to vanish, the first bonfire was lit on top of the hill which ignited a chain reaction across the country all the way to London to warn Queen Elizabeth of the approaching army. One hill after another was lit in a sequence stretching from the shore to the city. It wasn’t instant but it didn’t take long before the Queen knew what was happening miles away. Many hills in England were named “Beacon Hill” for serving as a signal for communication.

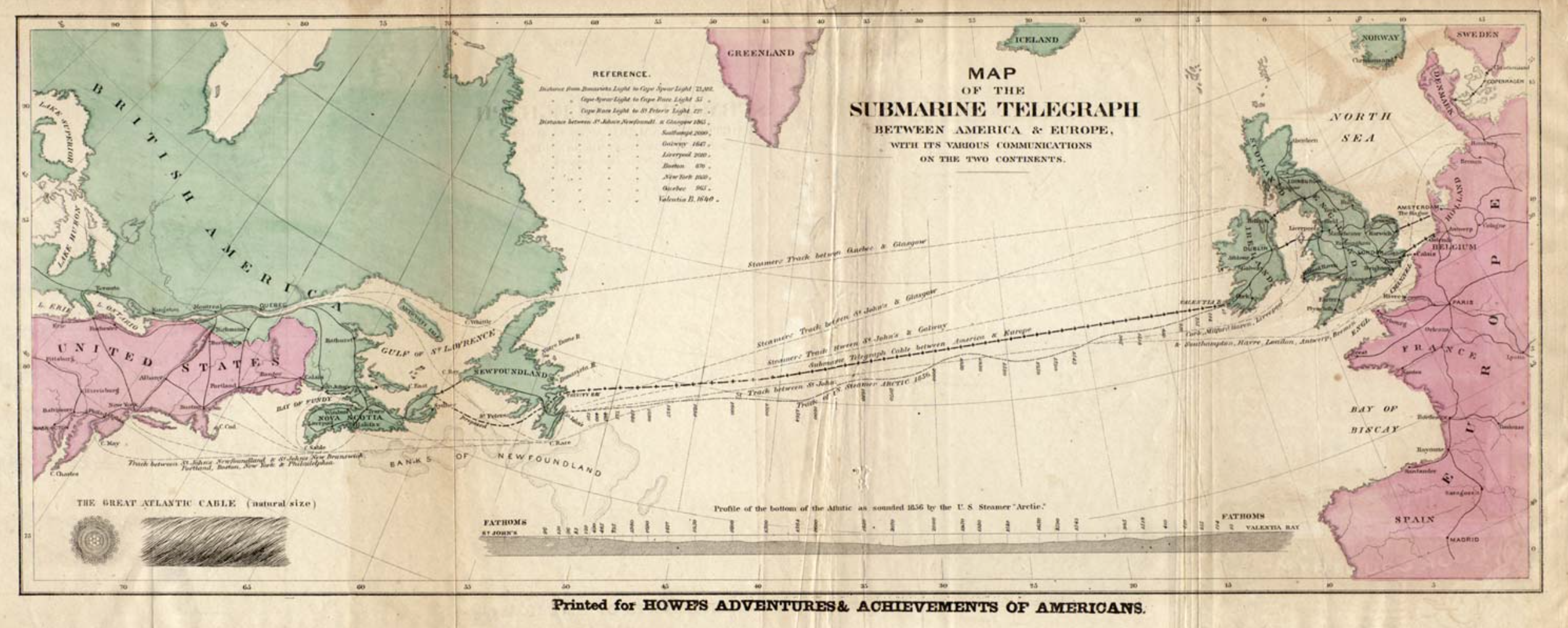

From early studies of electricity, electrical phenomena were known to travel with great speed, and many experimenters worked on the application of electricity to communications at distance. In 1753 an anonymous writer to The Scots Magazine suggested an electrostatic telegraph. In 1816 English inventor Francis Ronalds made it happen. He laid down 8 miles of wire insulated in glass tubing in his garden and connected both ends to two clocks marked with the letters of the alphabet. Electrical impulses sent along the wire were used to transmit messages. Then on July 27, 1866, the first transatlantic telegraph cable was successfully completed, allowing transatlantic telecommunication for the first time. The undersea cable ran under the Atlantic Ocean from Western Ireland to Newfoundland, Canada. Before the cable, it would normally take about ten days for communication between North America and Europe via ships.

Then came wireless telegraphy: the transmission of electric telegraphy signals without wires. It’s now used as a historical term for early radio telegraphy systems which communicated with radio waves (electromagnetic radiation). Wireless communication was established between Newfoundland and England in 1901 and by the 1920s, the transmission of speech made radio broadcasting possible. Can you imagine how the world must have reacted? Not since the dawn of the printing press had communication been more game changing. And then, in 1925, John Logie Baird was able to demonstrate the transmission of moving pictures at a London department store. Eventually, this led to the television.

In 2008 I sat in my college dorm room texting “Cha Cha” questions on my red T-Mobile flip-phone. Although the global economy was about to collapse, something bigger than the industrial revolution had already started. Less than three years later I was introduced to my first smartphone. I was hesitant to jump onboard, clinging to my flip-phone, not understanding why it would be necessary to need a mini-computer when a phone was used for nothing more than calls and texts. I remember my Uncle holding the brand new iPhone 4 in his hand saying, “But this thing… this will make you breakfast.”

Less than four years prior I started my first day of college classes as a print journalism major. I’m not sure if the major even exists anymore. I’ve always loved picking up and reading the physical newspaper and collecting magazines, from news to niches to literary publications. I was always drawn to print but I was living on the cusp of a digital revolution. I started blogging early, first on Xanga, then Live Journal, then Blogger, and finally my own WordPress site. Like most millennials, I was drawn to the web and social media from the start, yet it never shook my faith and love for the printed word. I still chose books over Kindles, treasuring my library of favorites, building and growing my collection for my future house and future family. I advanced in my major, passionate about my field of study, but the world was rapidly changing at a pace that couldn’t be emulated. It happened so fast it was hard to take full notice, grasp, or foresee what would come next.

By 2011 I was interning and working in Washington, D.C. I quickly learned a journalist would never survive, especially in the Capital, without a smartphone. If I wasn’t keeping up with the instantaneously digital breaking news, there was no way to make it. You either joined the rat race of sleeplessly updating and chasing news or you were left out. Regimented schedules no longer existed, even though they did just a few years prior. I watched as everything I learned, valued and revered about journalism turned on its head before my eyes as the lines blurred, daily morphing into something new because of technology. The world was facing the limitless and permanent. Breaking news went from a page one headline to a live tweet. One evening while at The National Press Club, I listened to Mona Eltahawy, an award winning columnist for The Toronto Star and The Jerusalem Report say:

“No country will see the end of it [social media] if the regimes are years behind what the younger generations are already on-top-of. These new tools are the ideal weapon for young people.”

Her words resonated with me as I checked my phone: a breaking news alert, a new tweet from one of my on-the-ground sources in Cairo, 2 new Facebook notifications, 1 missed text: MOTHER.

While I worked in Washington, the Internet and social media gave rise to the Arab Spring. The governments of Egypt, Tunisia, Libya and Yemen fell, and soon Tahrir Square came to Wall Street. The protests were much like the web itself: leaderless and limitless, a chaotic collective with no representative. It left the pre-web generation confused and inert. A world of transparency and a platform of free expression unlike anything ever before experienced in human history rivaled the invention of the printing press. Desperate attempts to control the web were launched with CISPA and SOPA bills. Behind our backs the NSA spied and collected data on everyone. But the spirit of transparency emerged when whistleblower Edward Snowden came forward and leaked the truth about our tragic loss of privacy.

I got my taste of the machine that is Washington and I absolutely loved it… until I wanted my life back. The thrill was exciting, but the cutthroat, superficial, work-till-you-die mindset of a morally compromised city had taken its toll and I decided that I didn’t want politics to be the rest of my life. I started to miss simpler times, and most of all I missed print.

In suburban Philadelphia where I grew up, a once popular mall stood vacant and eroding, doors shuttered, bearing graffiti. A tarnished brown, yellowing outline of what once read MACY’S could still be seen from the crumbling parking lot. Just a few short years ago the place bustled with customers but now the online shopping economy had conquered the building. I remember as a child sitting on Santa’s lap at Christmas and spending hours in the Border’s Bookstore, now just a name of the past having gone out of business due to online book shopping on sites like Amazon and the tilt toward a decline in print.

“Let’s hope movie theaters aren’t next,” a friend said to me one day as we passed the mall. “The day movies are released online, it’s over.” The thought made me sad. Despite being wildly overpriced anymore, going to the movies has always been a unique experience, waiting in line with crowds of people anxious to see the new release.

“What if drive-in movies made a comeback?” I said. “Wouldn’t it be awesome to see?” I only knew of one drive-in and I always loved going. It was a far better experience than the theater. “Honestly,” my friend said, “I think it would attract a niche group of people like us who found it cool and that’s about it. Everyone else would stay in and watch Netflix.” Unfortunately, I was inclined to agree.

Just a few years ago, when a person wanted a job they would get an internship and move up from there. They would read newspapers for job listings and they would network with the people they knew or stepped out to ask and meet people they didn’t. Flash forward a handful of years and jobs are now posted online to the entire planet. That company in your city that you’ve wanted to work for has opened up their vacant position that you’re more than qualified for to the entire world, not just your city or region. Suddenly you’re up against a whole slew of candidates and yet the saddest part is sometimes these positions are already filled because someone knows someone but the company needs to meet a quota of having interviewed and brought in so many people. Landing an interview means you’ll hear back from an automated “Thanks but no thanks” email in two or three months, or perhaps, just nothing at all. According to whistleblower attorneys, the potential exists to filter candidates to find what employers believe are only the best resumes, narrow them down and then find out who can be hired for the least. This is degrading.

People will say humanity has adapted to every advance in technology, from the printing press to telegraphy, television and now the Internet. They will say that each generation thought the new means of communication did more harm than good and that’s what’s being said today about the web. They’ll tell you it’s no different than the emergence of the telephone or the printed word and that to be fearful is silly. The difference is the telephone and the printed word never connected the entire world instantaneously. Never before in human history have people been able to instantly send and receive typed messages, videos, pictures and live stream themselves to nearly anyone anywhere on the earth. Truly it’s a beautiful and dangerous thing.

Netflix, Spotify, Airbnb, Facebook, Tinder, Uber, Lyft, Travelocity, Expedia, although all good things that save us money and grant convenience, come at the cost of devaluing or possibly eliminating jobs that used to provide these things. Who uses a travel agent anymore? And can you really blame the taxi cab drivers fury toward Uber? Philadelphia Inquirer journalist Will Bunch wrote:

“Journalists like me whine a lot about job losses in the newsroom, but I feel equally as bad about the rows of classified-ad takers down the hallway that have disappeared, thanks to free advertising on Craigslist.”

He went on to write that Spotify, Pandora and iTunes are supported by occasional ads or low-priced monthly subscriptions that pay artists pennies as opposed to the “good old days” when people bought CDs.

21st Century technology is so good it’s not creating jobs at the rate it’s destroying them. The now bankrupt Kodak once employed 140,000 people at its peak while Instagram employed 13. Tens of thousands of jobs have been shed by newspapers and magazines because people get news through Facebook, which employs a little over 8,000. Is there not a downward spiral to the rapid pace of technological advancement? Don’t get me wrong; I’ve jumped on the sharing economy bandwagon too, because I’ve had to.

But perhaps the most troubling and damaging aspect of all of this is the effect it has had on human relationships. With communication being destroyed under the guise of communication, we constantly miscommunicate through texts, emojis, and response time… I have to pause to say that great and wonderful relationships can be made possible due to the web. I have personally met incredible friends, sources and colleagues I would have never known otherwise, people who have encouraged, inspired and made lasting impacts on my life. I met the girl I love on Tinder and I’m forever thankful for it. But I can’t tell you how many times I so desperately wish I were talking to her on the phone as opposed to laying in bed texting. It’s not natural for our generation anymore. The seemingly infinite variety of people offered to us by Instagram, Facebook, Tinder, etc., leaves us with idealistic illusions, tailored photos and highlight reels of a persons life, unrealistic expectations and a repulse toward any kind of commitment. We think the grass is always greener, that there could always be someone else. Dating is no longer limited to a campus, high school or neighborhood as it was with our parents but now an entire world of opportunity lies behind the screen. We get lost in online subcultures and acquaintances. We record, snapchat and Instagram merely for the sake of impressing others, gaining followers, hoping the girls or guys we’ve taken a liking toward from upstate, the next city over or hundreds of miles away, view, like, or comment. At least my generation remembers life before all of this. I fear for those born into it. Are they even humans?

What happens when we become one with the Internet? When technology thinks and does everything for us? Do the people in Silicon Valley who are so preoccupied with whether or not they can ever stop to think if they should? Are we living the plot of Terminator or i-Robot in the form of these devices that could soon become implants? Does it really sound like a crazy conspiracy given the rate at which this has boomed?

“I don’t lose sleep over it,” my girlfriend said to me. She rarely posts and seems to keep up with just her friends. The thought gives me peace and encourages me to take a deep breath, abandon my own slavery, set the phone aside, pick up a printed book and read before going to bed. Maybe on our next dinner date we’ll leave the phones in the car and dare I say it, discuss, in detail, how our week went. Just the thought of lying in bed with nothing but each other and our books brings a comfort as warm as the bonfires that once stood on top of the hills in England, relaying a message of a simpler time, a simpler us, and we would be simply happy.